Investment Risks – Concentration, Volatility and Inflation Risks

Climber on top of a mountain

Introduction

The financial press is full of articles aimed at promoting anxiety amongst investors. Tuning out the noise, whilst difficult, is often the best course of action. However, we should all be aware of the different types of investment risk and I thought I would focus on three of these – concentration, volatility and inflation risk.

Concentration Risk

Most media coverage in this area focuses on US exceptionalism i.e. the outperformance of the US stock market over recent years along with the concentration in technology stocks known collectively as the ‘Magnificent 7’. These are:

Alphabet – the parent company of Google which leads in online search and advertising.

Amazon – e-commerce and cloud computing.

Apple – known for consumer electronics, particularly the iPhone, and strong brand loyalty.

Broadcom – a key player in semi-conductor technology and infrastructure software.

Meta Platforms – the parent company of Facebook and Instagram focusing on social media and virtual reality.

Microsoft – dominates the software market with products such as Windows and Office as well as cloud computing.

Nvidia – a leader in graphics processing units (GPUs) and artificial intelligence technology.

Let’s first look at the US stock market and whether it makes sense to hold a large proportion of investments in the US.

US Domination

The World equity market capitalisation, made up of all the companies listed on stock markets around the world, is worth around £73 trillion pounds. The US stock market accounts for around 65% of the world market capitalisation as of 31st December 2024.

Also as of 31st December 2024, Apple was the largest company by market capitalisation listed on the US stock market and it alone represented 4% of the world’s equity market capitalisation.

In comparison, the UK represents just 3% of the world’s equity market capitalisation. In other words, the value of Apple is more than the combined value of the companies listed on the UK stock market.

It is worth pointing out that we are not talking about the size of a country’s economy, the value of its exports or its GDP but simply the market capitalisation of the companies that make up its stock market relative to the world market capitalisation.

For example, China has a world market capitalisation of 3% which is smaller than that of Japan which stands at around 5%.

India has a world market capitalisation of 2% which is similar in size to France, Germany and Switzerland.

Based on the size of it market capitalisation, having a large weighting to the US makes sense as this is where most of the world’s great companies are listed.

The ‘Magnificent 7’

It is probably not surprising to find that the US stock market is dominated by the ‘Magnificent 7’ stocks, and they are all within the top ten stocks that make up the S&P 500 Index. Indeed, currently the top ten companies by market cap make up around 36% of the S&P 500 index.

The key question is whether this level of concentration is an anomaly or has it happened before.

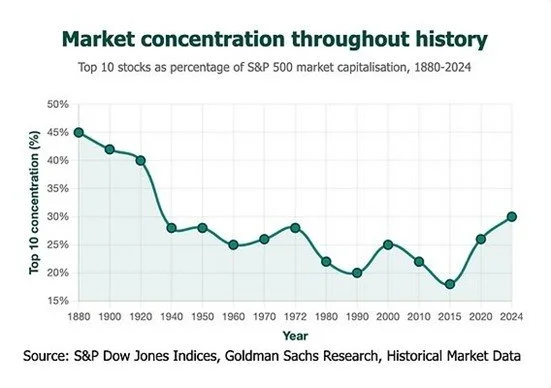

The following graph looks at how concentrated the S&P 500 index has been throughout history.

Market Concentration Throughout History

Although the current concentration of 36% is relatively high, it is not unusual for the top ten stocks in the S&P 500 index to comprise a relatively high proportion of the index.

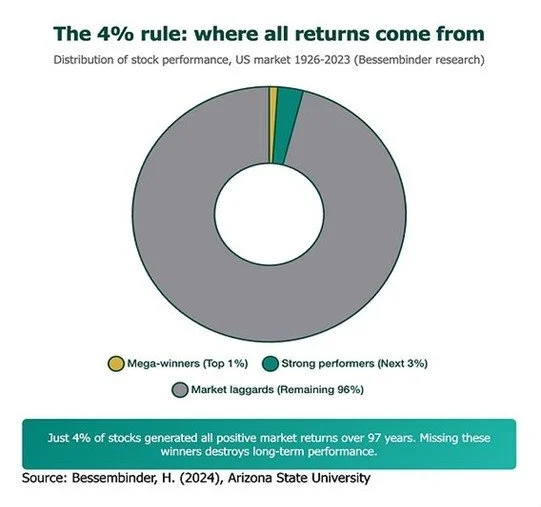

Let’s now drill down further into the historic returns of the S&P 500 index to see where the returns have come from. The following chart shows the distribution of US stock market performance in the period 1926-2023.

Market Concentration - the 4% rule

As you can see, over the 97-year period, market returns have been generated by only 4% of stocks which means that not holding those stocks will be detrimental to long-term performance. It probably also explains why equity fund managers who don’t have any exposure to the ‘magnificent 7’ stocks are finding it particularly difficult in terms of performance.

By holding all of the companies within the index, we have exposure to the mega-winners, the strong performers as well as the market laggards. What we can’t do, and the academic evidence suggests it is impossible to do, is to pick the mega-winners and the strong performers and to avoid the market laggards.

Concentration risk is therefore something that shouldn’t necessarily be avoided.

Volatility

Let’s look at volatility risk. Volatility is the risk that investments can go down as well as up in the short-term and is effectively the price all investors must pay for long-term performance. By way of an example, the S&P 500 index, from 1926 to 2022, provided an annual return of around 10%.

During this period, however, the index would have been up 71 times and down 26 times. In terms of calendar year returns, these ranged as high as up 54% and as low as down 43%.

Over the last 25 years or so, market corrections have tended to be short and sharp. Again, looking at the S&P 500 index, the bursting of the dot.com bubble in 1999/2000 resulted in a fall of 36% over a 12-month period but this was followed by a rise of 116% over the subsequent 62 months.

The S&P 500 index saw a fall of 51% over 13 months in 2008/2009 in response to the credit crisis but then saw a rise of 529% over the next 131 months.

Recently, the S&P 500 index saw a fall of 34% over one month at the start of the pandemic but subsequently returned 119% over the next 21 months.

It is important to remember that market corrections do happen but the biggest mistake investors can make is to sell out when markets fall.

Another mistake is to try and time the markets which means accurately forecasting both the top of the market (when to sell) and the bottom of the market (when to buy). This is nigh on impossible and can have an impact on long-term performance.

Let’s take a hypothetical $1,000 investment invested into the S&P 500 index on 1st January 1990. The investment would be worth $20,451 on 31st December 2020 if left fully invested. However:

If you missed the S&P 500’s best day the investment would only grow to be $18,329.

If you missed the best 5 days, the investment would only grow to be $12,917.

If you missed the best 15 days, the investment would only grow to be $7,080.

If you missed the best 25 days, the investment would only grow to $4,376.

The key message therefore is time in the market is better than trying to time the market.

We look to dampen down volatility within our portfolios by including an element of short-dated global bonds. For more adventurous clients we may have an 80/20 split between equities and bonds and for those less adventurous, we may have a 60/40 split between equities and bonds.

Inflation

It is worth bearing in mind that most of us invest for the long term in order to achieve an investment return in excess of inflation.

It often gets overlooked but each year the purchasing power of cash gets eroded by inflation because interest rates are typically lower than inflation.

Investing over the long term aims to provide a return in excess of inflation and this is the aim of all our investment portfolios.

If you are accumulating capital, typically your earnings will increase by at least the rate of inflation but if you are in retirement, you will need your pension to do the heavy lifting. This is great if you are lucky enough to have a Defined Benefit pension with its guaranteed income increasing in line with inflation each year but if you have a personal pension, a degree of equity exposure is needed to achieve a rate of return in excess of inflation.

This is why, in retirement, it is necessary to have an understanding of volatility and to build an investment strategy that can withstand market falls and still deliver the income required.

Conclusion

The biggest risk that we face, especially in retirement, is inflation and this is why we invest our money over the long-term – to achieve a return in excess of inflation.

It makes sense to hold an emergency fund in cash and in makes sense to hold cash for short-term goals, however, over the long term we need to take a degree of investment risk to achieve a return that exceeds inflation.

To be successful over the long-term we must accept that our investments can go down as well as up and that time in the market is more important than trying to time the market.

Contact Us

If you would like a review of your current investment portfolio or to discuss investments in greater detail, please do get in touch using the button below.